Understanding the weather isn't nearly as hard as some people try to make it out to be. Some people enjoy throwing out big terms like "synoptic" (a 50-cent word for "the big picture"), "hydrometeor" (a two-dollar word for raindrop), "adiabatic lapse rate" (you go up, the thermometer goes down), and--a perennial favorite among many who confuse polysyllabariatrics (big fat words) with actually knowing what they're talking about--"skew-T log-P diagrams" (a chart that is the weather equivalent of a Rorschach inkblot in that people look at them and try to decide if what they see is a bat, a skiing elephant, or their mother, then combine that with a handful of tea leaves and a rubber band to produce a forecast for yesterday's weather).

Despite my teasing of the users of skew-T log-P (often ever-so-helpfully shortened to just "skew-T") diagrams, which are actually very useful if you know how to interpret them in the same way that knowing how to rebuild a car's engine from scratch is useful if you ever need to drive to the grocery store, weather isn't big words or mysterious forces that make it gloomy one day and brilliant the next. Weather is one thing: weather is what happens when air masses squish into one another.

Even on days I'm not flying, I still check the weather out of old pilot habit. This weather check begins in a very unorthodox way, and I doubt you'd ever hear this way from your typical flight instructor, but it has served me well. Instead of first going to the "normal" weather sources like aviationweather.gov, weatherunderground.com (I like WU better than the Weather Channel's website because it is much faster to load, is less cluttered with irrelevant fluff, and it's easier to dig deeper into raw data if I'm in the mood to do so), DUAT/DUATS, etc., my first stop is to a website that wasn't even created for meteorology: the Wind Map at hint.fm/wind.

| |

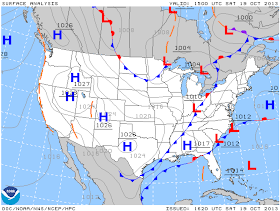

| The winds for October 19, 2013. Note the massive flow over the center of the country and the relatively lighter line stretching from Columbus, OH to Dallas, TX. |

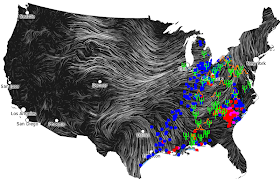

The Wind Map, once you learn to get a feel for it, tells you more useful information more quickly than a traditional surface depiction chart. This is pretty impressive considering that the creator calls it a "personal art project" and asks that it not be used to, among other things, fly a plane. But that's OK, because this is far from the only thing I'll use before I'll fly. It's definitely not something you'd use to make a go-no decision for anything at all, and there are a lot of things this can't tell you, many of which are very important (little things like ceilings and icing conditions).

What it is really good for is getting a feel for the big picture at a glance. "But isn't that what surface analysis charts and weather depiction charts are for," you might quite rightly ask. Sure they are, and you'd be crazy not to look at those before slipping the surly bonds of Earth. And, if you're planning to leave the traffic pattern (which means you'll be "not in the vicinity of an airport"), FAR 91.103 says it's not just a good idea to look at them, it's the law.

"Then what's the point of looking at this? Sure, it's got a trippy animation, but all I see are a bunch of wiggly lines. And this isn't even on the FAA written," you may complain. Sure it's not, but keep these two things in mind:

- Every pilot that died by flying into weather they weren't prepared for had passed the FAA written

- Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts, as Einstein probably didn't say

This is because where cold air comes barging through, we have a cold front. When warm air and cold air meet and fight each other to a stalemate, we have a stationary front. Where we have a low pressure system, we probably (but not always) have bad weather, but we always have air spinning around it counterclockwise, and vice-versa for a high pressure system.

Knowing just those basics, we can actually tell what the surface analysis will show before we even look at it, just by looking at the wind. Over Texas, we have a clockwise circle of air. That's a pretty obvious high pressure system. In the far north, we have a less obvious low pressure system. It's harder to see because the map cuts off at the border and only shows the southern half of the counterclockwise flow.

Over the middle of the country, wedged between the low to the north and the high to the south, we can see a huge flow of air being accelerated like a baseball between the two discs in a baseball pitching machine. It's flowing toward a line that stretches from around Columbus to Dallas, and east of Columbus it takes a sharp left and starts heading northward. This sharp, non-rotating turn means it's bumping into something else. It looks almost like water would if it hit a wall, doesn't it? And walls tend to be stationary things, right? Well then, it looks like we might have a stationary front there. Not only that, based on the sharpness of the turn and the speed of the wind that's hitting that wall, I'd venture a guess that there's going to be a decent case of the bumpies in that area. Think of all the splashing that happens when water hits a wall.

Now that we've taken a glance at the big picture, now we can move on and look at the "official" charts. Here's the surface analysis:

Look at that! A high pressure system right over Texas, a low pressure system over Minnesota, a stationary front over Ohio, and a cold front stretching from southern Ohio to the Texas coast. It's almost like magic, right? I mean, we knew that before we even looked at the chart.

Weather is what happens when air masses squish into each other, remember? And what's the technical, more elegant way of defining where are masses are squishing into each other? A "front". Developing this further, it's the cold fronts that tend to cause the most weather we care about as pilots.

So, can we extend our psychic superpowers even further and predict where the bad weather will be before looking at the next chart? Let's start by guessing that there's going to be cruddy weather from Ohio to eastern Texas because there's a distinctly lighter line of wind there on the wind map and there's a cold front there on the surface analysis chart. Now that we've taken a SWAG, here's the next one:

Feel like you're ready to start up a second career as a palm reader now? The blue dots all lined up like ducks in a row from Ohio to the Texas coast are cruddy weather. And what's more, there's something the wind map hinted at that the surface analysis chart can't easily depict: the orange wedges (interspersed with the green pitchforks) to the east of them show where the turbulence ("the bumpies" from five paragraphs ago) is.

Here's the satellite overlay so you can see the clouds:

And now, to really drive the point home, here's the original wind map overlaid with part of the map before last:

You can see that it only takes a few basic concepts combined with my First Law of Weather ("Weather is what happens when air masses squish into one another") to make people think you're a magician. OK, so it isn't quite that simple, but it's a big step in the right direction.

Weather is a lot like chess: the basic rules are very simple, but they lead to an almost infinite number of variations. That's why this post is called "Making Sense of Aviation Weather 1" and not "Everything You'll Ever Need to Know About Weather." However, most of those variations fall into some basic patterns, which means there will be plenty more to come on this topic in the future, and it also means you can get good at understanding the weather even if you can't tell a knight from a horsey. The next weather post will go into a warning about TAFs, and if you have any suggestions for topics you'd like covered or questions about what we just covered, please leave a comment below.

No comments:

Post a Comment