Follow on Twitter, too:

Follow @Lairspeed

In the last post, I had just started my first week in the actual aircraft as a newbie on IOE (Initial Operating Experience). This week, it's a new trip, same old thing: learning life on the line.

The FAA requires at least 20 hours of IOE in the kind of aircraft we fly. Since last week's trip wasn't 20 hours long, I get to do at least one more. We can technically do up to 100 hours (and some airlines do, just to ensure the 100 hours in the first 120 days requirement in (g) of the same regulation is met), but we typically receive 25-40 hours and then are signed off. That means I may be set loose on the line after this trip, or may get another one to ensure everything that needs to be covered gets covered. Since my first week on IOE was rather uneventful, that means there's still a lot left I haven't seen.

Personally, like most pilots I feel confident enough in my skills that I think I'll be ready after this trip is over. After all, the first week went well, and I'll only get better with experience. However, I'm not in a huge hurry to be released into base, because while I'm still on IOE status, the more annoying parts of the job don't affect me yet. I'm still deadheaded positive space to my assignments, meaning I'm guaranteed a seat to work. Once I'm signed off, I'll be flying on a standby space-available basis, which can be a pain sometimes. Also, I don't have to pay for hotel rooms, since those are still automatically covered should I time out or be cancelled in base. Those benefits vaporize as soon as I'm signed off.

The week goes smoothly, just as the previous one did. Too smoothly, in fact. Once again, everything went as it should operationally speaking. There were no maintenance issues, the weather didn't pose too many challenges (just the same air mass thunderstorm dodging as last week, with the exception of a major thunderstorm that rolled directly over Washington-Dulles—but even it got there a half-hour before we did, so it was already gone before we showed up), and there were no real air traffic delays. This trip, like the last, was the sort of four days every lineholder dreams about.

Until the last leg of the last day, when the weirdness at WEARD began.

Successful flights are all alike; every unsuccessful flight is unsuccessful in its own way. (Although Anna Karenina was written 30 years before the Wright Brothers' first flight, the principle that comes from its first line is one every pilot should ponder. After all, aviation is, as Wikipedia succinctly describes it, "...an endeavor in which a deficiency in any one of a number of factors dooms it to failure.")

That said, this isn't about an unsuccessful flight; it's about one that didn't go as expected up front. In the back, the passengers had no idea that anything was out of the ordinary, in large part because this was just an ordinary day going into the beautifully complicated airspace overlying Newark-Liberty International Airport. They also had no idea it was my first time ever flying myself in there.

We weren't originally supposed to be going to Newark in the first place. Our original Rochester-Dulles flight was replaced with a Rochester-Newark one for reasons only known to the crew scheduling department. That was fine with me, since I was looking forward to the challenge and the opportunity to learn something new. That's what IOE is all about!

Getting put into a holding pattern going into Newark isn't all that common, but it isn't out of the ordinary, either. Sure, the airspace over the NY 3 airports (Newark, LaGuardia, and JFK) is exceptionally congested, but ATC amazingly manages to fit all these fast metal tubes into their slots with less holding than one has a right to expect. They have several tricks up their sleeve to accomplish this.

One trick, which you've probably had happen to you if you've ever gone to one of the NY 3 later than approximately noon, is by ground stopping aircraft before they have a chance to take off. If you've sat in the airplane (or, with larger delays, sat in the boarding area and stared at the "Flight delayed until 5:30 p.m. for ATC" sign) at your original city until your wheels-up time, you've experienced this.

If the flow still gets too heavy, the controllers tend to give delay vectors instead of outright holding patterns. So instead of heading straight for the final approach fix, they may have you turn away from the airport anywhere from 30-180 degrees for a brief interval to open up some space and kill a bit of time. Often this means you're still heading generally toward the airport, but taking the long way there.

One of their last resorts is the holding pattern. Naturally, this means that I would get one on my very first time in! No problem: after all, entering holding patterns into the FMS is something we spent time on way back in the third week of ground school, right?

| |

| Ever wondered what the ground track looks like for a holding pattern? Now you know, thanks to FlightAware.com |

That doesn't look all that unusual, and it's not, except for one thing: that's not how I was supposed to fly that hold!

I am amazed and awed at how good a job New York Approach does in managing to get all their blips in a row, all day every day. Of course, one of the ways they keep it rolling is by being flexible, sometimes by the second. Another way is by having no patience with those who can't keep up. New York Approach is definitely no place for noobs. Which I was.

We were flying blissfully along, waiting to get to Newark and end a nice trip. Then, only 12 miles from WEARD intersection, we get this out of the blue (or, in this case, "into the blue"): "Clearance limit WEARD hold as published at WEARD expect further clearance 1650 time now 1615." [I left out any punctuation because punctuation implies that the controllers actually breathe when speaking.]

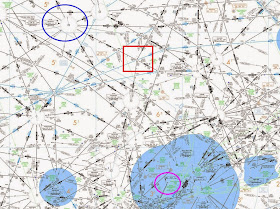

Notice that racetrack pattern northwest of WEARD? (There's a zoomed-in version below where it is probably easier to see.) That's the published holding pattern. And now I was 10 miles away from it. No problem in a car. Less easy in an airliner going almost 5 miles a minute.

|

| Once again, thanks VFRmap.com |

I had 2 minutes to program the hold into the FMS. It's a published hold, so the computer should know what it is, right? It knows all the holds during missed approach procedures, so why should it be any different for published holds en route?

As it turns out, and as I would learn, the FMS doesn't know any en route holds. When you program it, it just creates a holding pattern based on your current heading unless you tell it otherwise. In many cases, this amounts to the same thing as the published, since the chart designers often arrange it in such a way as to have the published hold be on the heading you're likely already on. (If we had been coming from the north, this would have indeed been the case here.) In this case, however, since we were coming from the northwest instead of the north, it wasn't the same thing at all.

And I had less than 30 seconds left to figure that out.

By the time I had my chart out and the intersection located, we were already in the holding pattern.

The wrong pattern, that is.

Notice that the racetrack next to WEARD was oriented generally north-south. What we actually flew looked like this:

|

| Once again, thank you FlightAware.com |

Fortunately, in this case it was no big issue. We were in the middle of nowhere (we were 66 miles away from the airport; not even in the same state as Newark), and the long EFC (Expect Further Clearance) time meant that they just wanted to keep us out in the middle of nowhere until something opened up. They didn't care how we twiddled our thumbs, as long as we stayed out of their hair.

As it turned out, we got extremely lucky, because we weren't even in the hold long enough for anyone besides ourselves to notice. As soon as we started our turn to start the second time around, we were told to continue on our way. And that's where the weirdness continued.

Everything was back to normal until we were getting close to landing. As it turned out, it was just a normal afternoon arrival into Newark, but since I'd never been there before, nothing about this afternoon was normal for me.

I was assigned 180 knots until 5 miles out. That's pretty standard at Newark, but definitely not a textbook approach for us. I handled it as well as could be expected for a first-timer, utilizing the turboprop's slow-down-and-get-down capabilities to my own fullest capabilities, managing a professional-quality landing. Nonetheless, I had to ask for some advice while doing so, and since this is something I'd be facing day after day on the line, we arranged for me to fly one more trip on IOE, this one going continuously in and out of Newark.

Which means one more week and I'm set loose on the line.

The author is an airline pilot, flight instructor, and adjunct college professor teaching aviation ground schools. He holds an ATP certificate with a DHC-8 type rating, as well as CFI, CFII, MEI, AGI, and IGI certificates, and is a FAASafety Team representative and Master-level participant in the FAA's WINGS program. He is on Facebook as Larry the Flying Guy, has a Larry the Flying Guy YouTube channel, and is on Twitter as @Lairspeed.

It takes hours of work to bring each Keyboard & Rudder post to you. If you've found it useful, please consider making an easy one-time or recurring donation via PayPal in any amount you choose.

No comments:

Post a Comment