METARs, TAFs, and other sources of aviation weather give the heights of cloud bases, but they do not give any information about what kind of clouds they are. The sole exception that you're likely to see is CB—cumulonimbus. After all, thunderstorms are important to know about because you don't want to fly into one. However, there is another exception, one that you're unlikely to see in your average everyday flying: FC—funnel cloud. Lee Sandlin's book is all over these and the people who study them, chase them, and obsess about them.

Ben Franklin is known for many things, and one of the images that probably comes to mind when you think of the name is the painting of him performing the famous key on a kite experiment. What you may not have known is that the author of Poor Richard's Almanack was also the author of studies on tornadoes and waterspouts, making him one of the founders of what would eventually become the modern science (and Weather Channel overdramatization) of storm chasing.

|

| From one of Franklin's studies called "Water-spouts and Whirlwinds". Photo from NOAA's Photo Library at http://www.flickr.com/photos/noaaphotolib/ |

Along the way, he takes us on visits to the trails of destruction left by tornadoes, which were then known as "wind roads" as they cut passages through the thickly-wooded lands of the early United States. Until the invention of the airplane, research on these was only able to be done slowly by painstakingly walking them and taking notes on the arrangement of debris. Ted Fujita (the "F" in "EF-5 tornado") was able to make much of the progress that he made by utilizing Cessna planes to fly him along these trails.

Sandlin gives us an account of the Peshtigo firestorm which spawned tornadoes of flame, incinerating villages and killing more people than any other fire in U.S. history. (The fire made the public relations blunder of happening on the same day as the Great Chicago Fire, which is why it's likely you've never heard of it despite its apocalyptic style.)

He drops in on Tinker Air Force Base and relates the story of the first successful prediction of a tornado, takes us to the Weather Bureau when it fit in a single unremarkable building, and recounts the damage done by several different tornadoes of historical proportions, and does almost all of it so well, with such good tie-in, that it's almost as much of a page-turner as a fiction novel would be.

In fact, the only real complaint is that once we go on this tour through a few centuries of storm-chasing history, he closes up shop and turns off the lights as soon as we get to the present day storm chasers. I can't fault him overly much for this for two reasons. First, there are several books already on the market about modern storm chasing, many of them written by the chasers themselves. Second, the book, by its very title, is intended to be a history of storm chasing, which means its subject matter excludes the present. True to form, almost the only mention made of modern storm chasing is in a rather short epilogue.

Summary: A fast read that is surprisingly entertaining for a history book. If you buy it through the link below, you help support Keyboard & Rudder at no cost to you:

What Sandlin left out was that tornadoes also happen on Mars. They even leave their own "wind roads", though theirs are through the dusty surface of the red planet instead of fallen trees. Check out the two images below for proof of extraterrestrial tornadoes:

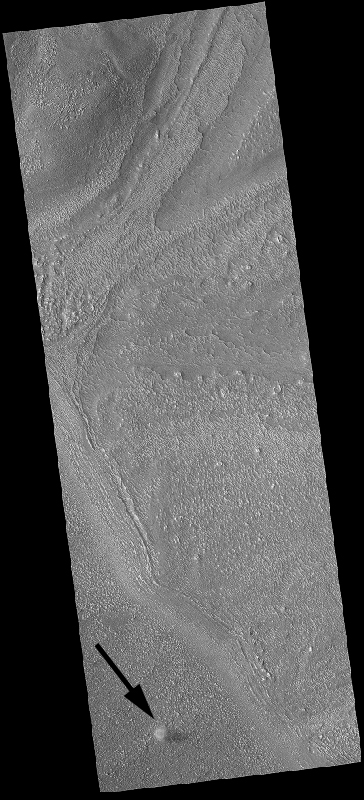

| |||

| The arrow is pointing at a Martian dust devil. See http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSP_004285_1375 for more information. |

| |

| The black squiggles are Martian "wind roads" created by dust devils as they wandered the surface, kicked up dust, and faded away. See http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/ESP_013538_1230 for more information. |

No comments:

Post a Comment