Surprisingly, plenty of other people in deadly scenarios don’t act fast enough to save their own lives. From arguing over small change while a ship sinks into stormy water, to standing idly on the beach as a tsunami approaches, psychologists have known for years that people make self-destructive decisions under pressure. Though news reports tend to focus on miraculous survival, if people escape with their lives it’s often despite their actions – not because of them.It goes on to list several things you should not do in an emergency:

"Survival training isn’t so much about training people what to do – you’re mostly training them not to do certain things that they would normally think to do," says John Leach, a psychologist at the University of Portsmouth who survived the King’s Cross fire disaster in 1987. He estimates that in a crisis, 80-90% of people respond inappropriately.

- Freezing

- Inability to think

- Tunnel vision

- Staying stuck in routine

- Denial

For [disaster management specialist James] Goff, surviving a natural disaster is about having a plan. "If you know what you’re doing in advance and you start early, you can usually get away from a tsunami," he says. "But it might be a bit hairy."That last sentence is the important take away. You need to have a plan and practice that plan until it is automatic. When you're confronted with an emergency is not the time to come up with something. You need to have come up with that something from the comfort and peace of your own home, then drilled it until it becomes automatic.

Leach has years of experience training the military to escape an eclectic mix of chilling scenarios, from hostage crises to helicopters which have crashed into water (top tip: stay in your seat until the fuselage has flooded and turned upside down, then slip out at the last minute to avoid getting caught in the still-turning rotor blades). He knows that the best way around the mental fallout is to replace unhelpful, automatic reactions with ones that could save your life. "You have to practise and practise until the survival technique is the dominant behaviour," he says. [Emphasis mine; weird British spelling the BBC's.]

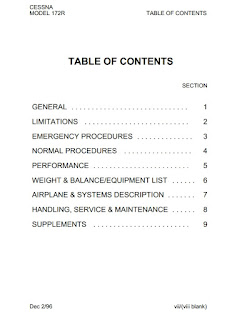

This is why I recommend reviewing your Pilot's Operating Handbook's third section periodically. What's the third section? Naturally, the emergency section. (In 1975, the General Aviation Manufacturer's Association issued Specification No. 1 standardizing the layout of the POH, so you'll probably find the emergency/abnormal procedures in Section 3.)

|

| This index from the manual for a Cessna 172R is in the standard format. |

Go through the procedures and make a small goal of memorizing one every week or two. It's actually pretty easy to accomplish. Simply make a flashcard with the procedure you're memorizing and put it on your nightstand. When you lay down, go over it a few times. Then—and this is very important—close your eyes and visualize yourself doing each of the steps.

With your eyes closed, see yourself pitching for 65 knots. See the attitude out the window and feel yourself trimming the plane to hold that. See yourself touching and pushing in the fuel shutoff valve. See yourself touching and looking at the fuel selector valve to ensure it is on BOTH. And so on.

The visualization process is critical to making your response automatic. One of the two reasons I recommend doing this just before bed is that you won't feel silly laying in bed with your eyes closed. The second reason is that piles of scientific research have shown that what we study just before bed is what is stored away the strongest.

Much research has also shown that visualizing the process in your mind activates many of the same regions of the brain as actually performing the task does. In this way, you get almost as much practice benefit as if you were actually in the aircraft.

The goal here is automaticity. You want to make the process so ingrained that it requires little to no thought to respond correctly. This eliminates three of the "not to do" bullet points above: freezing, inability to think, and tunnel vision. By making your emergency procedures automatic, you won't freeze; you'll just do what comes naturally. You don't want to have to think about what to do because your cognitive ability shrinks dramatically in an emergency, and you won't have to worry about tunnel vision.

Now that we've talked about how not to kill yourself in an emergency, next week will be a short post about killing yourself to learn to fly. See you next Wednesday!

Like Larry the Flying Guy on Facebook:

Follow @Lairspeed

The author is an airline pilot, flight instructor, and adjunct college professor teaching aviation ground schools. He holds an ATP certificate with ERJ-145 and DHC-8 type ratings, as well as CFI, CFII, MEI, AGI, and IGI certificates, and is a Master-level participant in the FAA's WINGS program and a former FAASafety Team representative. He is on Facebook as Larry the Flying Guy, has a Larry the Flying Guy YouTube channel, and is on Twitter as @Lairspeed.

It takes hours of work to bring each Keyboard & Rudder post to you. If you've found it useful, please consider making an easy one-time or recurring donation via PayPal in any amount you choose.

No comments:

Post a Comment